read time = 10 minutes

Summary

Domain names are strings that define an association to an Internet Protocol (IP) resource. They may represent any website, server, or client host attempting to communicate via the internet. Anyone using the internet encounters them everyday as they are simply the letters that come after the [dot] in an internet address (such as .com). These names are used as common identifiers that resolve to IP addresses, and are intended to be significantly easier to remember. Domain names are organized in a hierarchical structure called the domain name system (DNS) that includes the DNS root domain, top-level domains (TLDs), second-level domains, and so on.

Top-level domains typically represent certain administrative categories or industry segments, such as .com, .org, and .edu. All TLDs include the “legacy” generic top-level domains (gTLDs), “new” generic top-level domains (nTLDS), in addition to country code top-level domains (ccTLDs), all of which are considered the highest-level domain names within the DNS.

TLDs are important because the DNS system is frequently abused by threat actors to host malicious resources, launch phishing attacks, and trick victims into performing risky actions. New malicious websites hosted on suspicious TLDs are created once every 15-20 seconds, and most are used within only a few hours before operators refresh their infrastructure. Attackers are creating and disposing of the various domains they acquire quickly and easily.

For a variety of reasons, including cost and legal considerations, certain TLDs are used and abused more frequently than others. The goal of this report is to establish a list of the riskiest domains that threat actors are most likely to abuse. The implication here for detection and prevention efforts is the identification of suspicious domains that may be good candidates for further analysis, or even inclusion in a blocklist for email firewalls, proxy servers, and/or other security controls.

OSINT Research and Analysis

Background on a Growing Threat

In 2012, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) introduced a new program to introduce “new” TLDs (nTLDS) to the DNS name space in order to increase flexibility and choice for domain registrants. Over 1,000 new TLDs were introduced with this program. Just 10 years ago, there were only 20 generic domains, which most are familiar with, comprised of .com, .org, .net, and so on. These are now considered “legacy” generic domains (gTLDs). Today there are over 1,500 total TLDs after the addition of the “new” nTLDs. An annotated root zone database containing all of these domains is curated by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

Domain names are an important resource for organizations to establish a unique brand identity for their online presence. However, this system can easily be abused by threat actors who register typo-sqautted domains with spoofed or names to take advantage of these recognizable brands. These domains could be used to deliver spam emails, host credential phishing websites, or stage malware payloads that are downloaded onto the victim’s system.

The massive growth in available TLDs with the “new” TLD program has led to a corresponding increase in fraudulent domain registrations leveraged for nefarious purposes. Many of the “new” nTLDs and/or ccTLDs can be registered very cheaply or even for free in many cases. This is obviously very attractive for threat actors as many of them operate at scale, so the capability to register a high-volume of domains without committing additional resources ultimately leads to a higher return on investment (ROI) from their campaigns. A recent report from Group-IB Intelligence suggests that potentially fraudulent domain registrations have increased 37% since the implementation of the “new” TLD program.

Use of Domain Names for Phishing

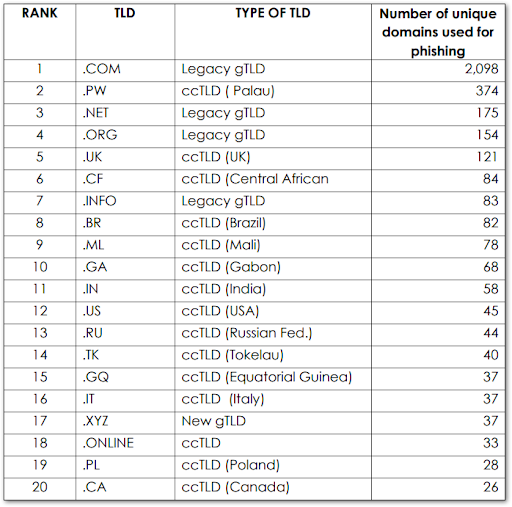

Before determining the riskiest TLDs from a defensive perspective, it is useful to first identify the TLDs that are being abused for malicious purposes. The Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) identified the following domains in their Phishing Activity Trends Report, 1st Quarter 2019:

RiskIQ researchers analyzed a sample of over 6,000 malicious URLs reported to the APWG in Q4 of 2018, and identified 4,485 unique second-level domains. These metrics were based purely on the total amount of malicious sites mapping to the TLDs.

gTLDs – “Legacy” generic TLDs

Common or generic domains such as .com, .org, and .net represented 56.43 percent of the phishing domains in the sample set. The .com domain accounted for 2,098 domains in the set.

This is not surprising as these TLDs account for approximately half of all website domains, so their volume will naturally be high. This volume of malicious phishing in some of these TLDs is expected – for example, .com, .net, and .org are all long established gTLDs with very high numbers of website registrants among them. It is expected purely by volume that a correspondingly large number of websites would be vulnerable to attack and thus compromised. These sites are then leveraged to host malware or deliver malicious mail.

nTLDs – “New” generic TLDs

Other domains such as .xyz and .online represented 4.95 percent of the domains in the sample. There was a total of 222 nTLDs in the data set.

For the new TLDs in this research sample, .xyz, .top, and .loan represent the highest volume of domains associated with malicious activity. It is unclear why these in particular have been utilized, as they do not stand out in any particular way, nor is there any apparent financial incentive to registering these domains. It is possible that .xyz and .top are leveraged simply because they are mundane and less likely to arouse suspicion in a potential victim. The .loan domain makes some sense as many phishing campaigns leverage a financial theme in their lure templates. Namecheap and GoDaddy are some of the top registrars used for registration of both gTLDs and nTLDs.

ccTLDs – country-code TLDs

Specific country domains, such as .uk for the United Kingdom and .RU for Russia represented 38.62 percent of the domains in the sample, for a total of 1,732 ccTLDs in the data set.

Many of the ccTLDs on the above list may seem counterintuitive because there is no obvious volume component that would dictate a high malicious usage. For example, Palau, Mali, and Tokelau are smaller countries and there is no inherent feature of these countries that would contribute to a high number of malicious registrants. This is not to say that there is no reason for their high usage. Many of these countries have “repurposed” their country-code domains and essentially transferred the management rights and administration of their TLDs to third parties such as Freenom. These ccTLDs are then made available (often for free) to any customer, including threat actors. Many of the ccTLDS – .tk, .ml, .ga., .cf, .pw – on APWG’s list are available for free.

A separate list from researchers with Wandera security, evaluated their top 5 TLDs used for phishing attacks and revealed multiple consistencies:

- .com – the most prevalent domains and the global standard for doing business online.

- .ga – the country-code for Gabon, a sovereign state in Africa. Available for free on Freenom.

- .tk – the country-code for Tokelau, a territory in the South Pacific. Available on Dot TK for free.

- .ml – the country-code for Mali, another country in Africa. Available for free on Freenom.

- .cf – the country-code for The Central African Republic. CA telecom has a partnership with Freenom and registrations are free and essentially unregulated.

Even though a phishing campaign hosted on .com may be more likely to be successful due to its familiarity and trust, this would be favored by actors deploying a targeted campaign. High volume phishing campaigns commonly leveraged thousands of domains, and not many threat actors are well-resourced enough to make that kind of investment. Consequently, for high-volume, opportunistic campaigns at scale that rely on small margins of success, it is preferable to leverage the free TLDs to keep operating costs down.

A Survey of Quantitative Risk Analysis Methodologies

There are multiple online resources that track and attempt to assess the risk posed by various top level domains. The specific analysis methods vary from each resource, but most are based on some form of measurement of the total number of registered domains, or the percentage of registered domains within a particular TLD that are used for malicious purposes.

There are drawbacks to this type of methodology, one of which is that for a domain to be scored as malicious, some evidence of activity associated with nefarious behavior must first be observed, whether it be the hosting of a phishing site, delivering a malware binary, or sending spam. Another complication includes the misleading nature of very popular domains such as .com that because of their popularity have high numbers of malicious domains, but are not inherently risky. A second approach is to develop a risk metric based on the proportion of malicious domains within a TLD that compared to the total count of domains. Further, both of these approaches still rely on prior weaponization, but a possible solution to this reactive scoring methodology is the development of the “Threat Profile” by Domain Tools, which attempts to specify a domain’s riskiness using machine learning algorithms to predict how risky certain domains may be before they are deployed in a malicious campaign.

Spamhaus: The Top 10 Most Abused TLDs

The Spamhaus Project is an online resource that tracks spam and related cyber threats such as malware, phishing, and botnets and assigns a relative risk score or “badness index” to measure the riskiness of domains. They maintain a running list of the top 10 “most abused” TLDs.

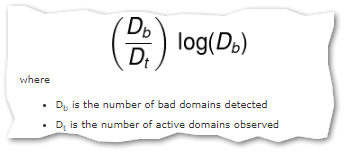

They define “badness” as a function of the total number of bad domains of a certain TLD divided by the number of active domains observed within a TLD. The quotient is then weighted against the TLDs’ size.

The logarithm contains a certain amount of arbitrary weighting, but ultimately attempts to reduce the skewing of very large TLDs that may contain a high volume of malicious domains, and very small TLDs that may have low volume but a high proportion of malicious domains, but limited impacted based on their small size.

Most TLD registries actively regulate their registrars attempt to keep abusers off their domains and maintain a positive reputation. The implication being that TLDs making their Top 10 are not putting in enough effort to dissuade spammer and abusers and may actually be profiteering off such activity.

According to Spamhaus:

“The registries which allow registrars to sell high volumes of domains to professional spammers and malware operators in essence aid and abet the plague of abuse on the Internet. Some registrars and resellers knowingly sell high volumes of domains to these actors for profit, and many registries do not do enough to stop or limit this endless supply of domains.”

Symantec’s Shady 20

Symantec also publishes a ranked list that defines their “top 20” shady top level domains. The firm historically released their list once year, but the most recent entry was from March of 2018. Symantec, owning both WebPulse and Bluecoat proxy services has some valuable insight into how domains may be used maliciously and categorized.

Similar to Spamhaus, Symantec’s shady rating is a calculation based on a ratio of domains ending with a particular TLD that are rated in their systems as “shady” and divided by the total number of database entries for that TLD. The shady rating is presented as a raw percentage and is not weighted for TLD size, or impact considerations.

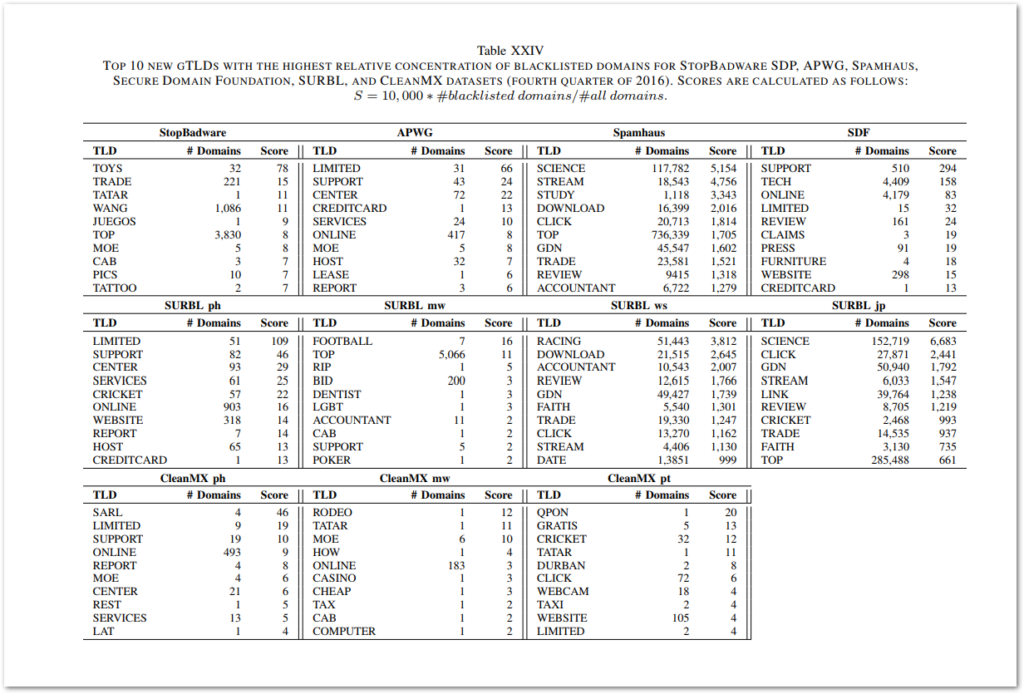

Statistical Analysis of DNS Abuse in gTLDs: Delft University of Technology

ICANN commissioned an academic study by a review team that focused on an attempt to measure several metrics and identify rates of the most common forms of DNS abuse. The comprehensive study analyzed malicious behavior within the global DNS system and then compared rates of malicious activity within new (nTLDs) and legacy (gTLDs) generic top level domains. Their findings suggest that abuse rates of some of the nTLDs have risen and gTLDs have fallen, but overall domain abuse with malicious domain registration does not appear to be significantly increasing. Essentially, the nTLDs are displacing gTLDs as the favored domains for utilization in abuse activities. The report makes a descriptive statistical comparison of DNS abuse in nTLDs and legacy gTLDs as they relate to spam, phishing, and malware distribution. Hesselman et al., state:

“Moreover, while legacy gTLDs collectively had a spam-domains-per-10,000 rate of 56.9, in the last quarter of 2016, the new gTLDs experienced a rate of 526.6–which is almost one order of magnitude higher. The analysis of the three most abused new gTLDs show that 51.5%, 47.6% and 33.4% of all registered domains were abused by cybercriminals and blacklisted by Spamhaus in the last quarter of 2016.”

Abuse of DNS does not affect all nTLDs. The statistical analysis of Spamhaus and SURBL blacklists indicates that at least 33% of all nTLDs that are available from registries do not experience utilization for malicious purposes. However, at least 10% of such nTLDs were blacklisted by Spamhaus during the reporting period. Further analysis indicates that criminals also prefer to register standard nTLDs, which are generally open to anyone in the public, over “community” nTLDS such as .radio or .pharmacy, which may impose strict restrictions on who can register.

Hesselman et al. use what they describe as an “occurrence series” of security metrics to calculate the “badness” of a particular TLD. These abuse metrics examine domains and the amount of TLD badness with specific, distinct criteria for second level domains, fully qualified domain names (FQDN), and uniform resource locators (URL). The badness metric is normalized against the size of the domain. The researchers do not account for ccTLDs in there calculations.

Figure 6: Top 10 new nTLDS for various blacklists.

Domain Tools Threat Profile

Threat Profile is a risk scoring methodology developed by domain tools that uses machine learning analysis to provide insight into TLD riskiness. This approach fundamentally differs from the previous ones presented in this report as it is based on predictive algorithms instead of blacklists of known malicious domains within particular TLDs. The primary advantage of this approach is it is proactive as opposed to reactive, and would theoretically identify risky domains before they have been weaponized. According to Domain Tools, the Threat Profile analyzes:

“data from over 300 million domains in our database to create a set of 3 machine learning algorithms to predict how likely a domain was created for malware, phishing, or spam purposes.”

Domains are scored on a scale of 0-100 to measure their riskiness. Distributions can be plotted graphically and compared via “clustering” to identify those TLDs with a high concentration of risky domains. The full source code, data, and results of the cluster analysis can be found on Domain Tools’ GitHub here.

Conclusions | Recommendations

These findings suggest that many new nTLDS and ccTLDS have consistently grown in interest as a target for malicious threat actors. Low to free pricing models, unregulated registry practices, privacy services, and a variety of other registration options such as flexible payment methods and bulk provisioning have contributed to a shift away from the larger, legacy gTLDS. To further complicate issues, some registrars actively profit on these questionable practices and appear to be unconcerned with maintaining positive reputations for certain TLDs. These business practices have lowered the barrier of entry for a wide swath of cybercriminals, and have contributed to the growing threat from phishing and malware campaigns operated at scale.

One approach to reducing risk from these types of threats leveraging malicious TLD registration is to focus on the riskiest TLDs and attempt to block them, or develop detection rules and alerting based on potentially suspicious interactions with these domains. I have aggregated all of the various blacklists examined for this report and weighted individual TLDs based on the number of occurrences on those lists. The domains listed below represent the riskiest TLDs from this combined data. For the purposes of this ranking, a higher occurrence only roughly translates to a higher perceived risk. NOTE: I strongly recommend reviewing the business impact and feasibility of blocking these domains before deploying countermeasures with security controls such as proxy servers, email gateways, and/or firewalls.

Caveats

This is not a blocklist. I also caution against extrapolating too much into the relative positions of various TLDs on this list. For example, the highlighted TLDs above in RED are ccTLDs available for free on DOT TK or Freenom and are highly abused by threat actors, and may represent a higher absolute risk than TLDs ranked above them here (in my opinion). Also, rankings may be very fluid from quarter to quarter, or year to year and so a reassessment of risky TLDs is recommended to be conducted on a regular basis. Again, I am not advocating setting up blanket policies to block all of these TLDs outright. This data should simply be used for context and as a jumping off point for further analysis. Any recommendations for blocking requires additional research into a particular TLD and consideration of the particular circumstances of an organization, its potential business impacts, and risk appetites.

References

[1] https://www.iana.org/domains/root/db

[2] https://www.group-ib.com/media/gib-fifa-2018/

[3] http://docs.apwg.org/reports/apwg_trends_report_q1_2019.pdf

[4] https://www.wandera.com/mobile-security/phishing/phishing-top-5-tlds/

[5] https://www.avanan.com/hubfs/2019-Global-Phish-Report.pdf

[6] https://www.spamhaus.org/statistics/tlds/

[7] https://www.symantec.com/blogs/feature-stories/top-20-shady-top-level-domains

[8] https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/sadag-final-09aug17-en.pdf

[9] http://www.surbl.org/tld

[10] https://www.hesselman.net/publicaties/SPEurope2017Korczynski.pdf

[11] https://blog.domaintools.com/2019/05/using-domaintools-threat-profile-to-identify-risky-tlds/

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cluster_analysis

[13] https://github.com/DomainTools/risky-tld-cluster-analysis